https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/Swearing-In-Austin-and-Brian.jpg

480

640

Mike Bullis

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

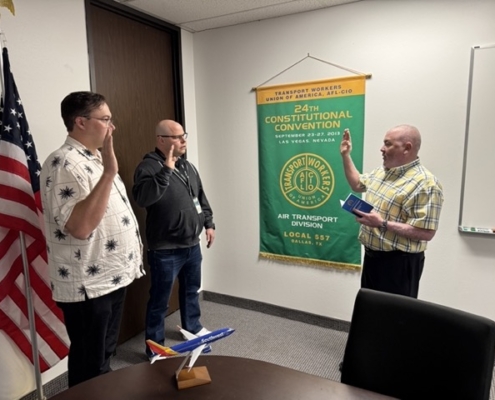

Mike Bullis2025-04-01 13:55:282025-06-23 16:12:47New TWU557 Board Members Appointed Apr 1, 2025

https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/Swearing-In-Austin-and-Brian.jpg

480

640

Mike Bullis

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Mike Bullis2025-04-01 13:55:282025-06-23 16:12:47New TWU557 Board Members Appointed Apr 1, 2025 https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/Jim-Baird-with-Jose.jpg

640

480

Mike Bullis

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

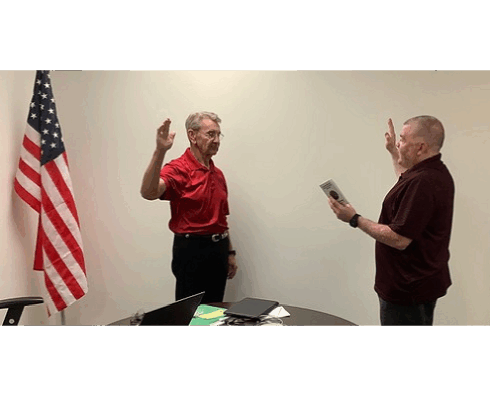

Mike Bullis2025-04-01 13:18:562025-06-23 16:13:01Capt Jim Baird Recognized For TWU557 Service

https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/Jim-Baird-with-Jose.jpg

640

480

Mike Bullis

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Mike Bullis2025-04-01 13:18:562025-06-23 16:13:01Capt Jim Baird Recognized For TWU557 Service https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/DaleySwearingIn3-Medium.png

480

640

Mike Bullis

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Mike Bullis2024-09-07 08:40:172025-06-23 16:33:25Greg Daley, New Member At Large

https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/DaleySwearingIn3-Medium.png

480

640

Mike Bullis

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Mike Bullis2024-09-07 08:40:172025-06-23 16:33:25Greg Daley, New Member At Large https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/SM_Jay-JC-and-Jose.jpg

1125

1500

Gordy

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Gordy2024-04-01 06:24:212025-06-23 16:33:39New Board Members as of April 1, 2024

https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/SM_Jay-JC-and-Jose.jpg

1125

1500

Gordy

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Gordy2024-04-01 06:24:212025-06-23 16:33:39New Board Members as of April 1, 2024 https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/JimBaird_Nov5e_sq.png

500

500

Gordy

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Gordy2021-11-25 10:59:222025-06-25 21:56:29Jim Takes Robert’s Vacancy, Officially Becomes TWU557 President

https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/JimBaird_Nov5e_sq.png

500

500

Gordy

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Gordy2021-11-25 10:59:222025-06-25 21:56:29Jim Takes Robert’s Vacancy, Officially Becomes TWU557 President https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/SM_Jerry-Award-from-Jose-e1750526464559.jpg

800

600

Gordy

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Gordy2021-11-23 10:34:552025-06-23 16:34:16TWU557 Past President, Jerry Bradley, Recognized For His Service

https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/SM_Jerry-Award-from-Jose-e1750526464559.jpg

800

600

Gordy

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Gordy2021-11-23 10:34:552025-06-23 16:34:16TWU557 Past President, Jerry Bradley, Recognized For His Service https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/Swearing-In-Simonds-Robert-Jim-Joe.jpg

423

800

Gordy

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Gordy2021-04-01 11:07:032025-06-21 11:17:44TWU557 Newly Elected Officers April 1, 2021

https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/Swearing-In-Simonds-Robert-Jim-Joe.jpg

423

800

Gordy

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Gordy2021-04-01 11:07:032025-06-21 11:17:44TWU557 Newly Elected Officers April 1, 2021 https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/3.webp

630

1500

Gordy

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Gordy2019-06-04 11:23:072025-06-21 11:32:17Professional Data Returned by Instructors

https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/3.webp

630

1500

Gordy

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Gordy2019-06-04 11:23:072025-06-21 11:32:17Professional Data Returned by Instructors https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/Jim_Parker_sq.png

500

500

Gordy

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Gordy2019-01-27 11:49:352025-06-25 12:06:45SWA Employee News

https://www.twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/Jim_Parker_sq.png

500

500

Gordy

https://twu557.org/wp-content/uploads/logo.webp

Gordy2019-01-27 11:49:352025-06-25 12:06:45SWA Employee News